Chorus - The under dog effect everyone loves

Sam LooseAt its core, a chorus effect operates by duplicating an incoming signal and slightly modulating the pitch and time of the duplicated signal before mixing it back with the original. This slight pitch and time variation between the two signals creates a lush and shimmering sound, similar to the sound created by a choir, where each voice is ever so slightly different in timing and pitch. But aside from the technical ins and outs, chorus is an effect that creates an ethereal sound and puts the audio in a completely different space.

You only need to listen to modern acts such as Tame Impala to hear chorus at play. The way the vocal soars out of the speakers and lands in the listener's ear wrapped in a silk sheet that invites them in to listen some more. But chorus isn’t reserved solely for elegant vocals, you’ll hear it soaking any number of guitar tracks throughout the history of modern recorded music, from The Police’s “Message In A Bottle” to Nirvana’s “Come As You Are”. Each has its own unique sonic signature, but each has a familiarity that grounds the listener and lets them know they’re hearing an old friend.

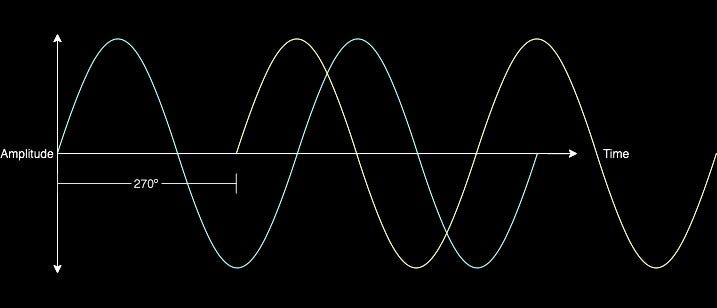

The chorus effect has some not so distant cousins that often get mistaken for each other: the Flanger and the Phaser. All three have similarities in their construction, but give a notably different result. The chorus is more of a shimmering sound with a sense of space, as if multiple voices or instruments are intertwined, but differing very slightly, creating the effect itself. These differences are imparted on the duplicates of the original signal by modulating with an LFO (Low Frequency Oscillator) A chorus’ delay times can vary from as low as 5ms to as high as 30ms and sometimes beyond; these differences in delay times are where the different favours of chorus can be heard, and these parameters will be altered to suit the song.

A flanger uses a far shorter delay time in its duplicated signal. Usually around 1ms-5ms as opposed to a chorus’ 5ms-30ms. As a flanger only uses one duplication of the original sound, it can cause interference at certain frequencies between those two copies, whereas in a chorus there are often multiple copies, so the effect of the interference is minimised and can be hidden somewhat. This effect is steeped in studio history. During playback from two tape machines, an engineer would press down slightly on the edge of one of the tapes. This applied pressure and made a short delay, which meant that machine would have to catch up and re-synchronise with the master machine, and the unique flanging effect could be heard.

The phaser falls somewhere in between a chorus and a flanger but with one key difference: it doesn’t modulate delay time. A phaser modulates the phase of an audio signal, creating sweeping, swirling sound with notches in specific frequencies by using an all-pass filter. A great example of a phaser in action is the opening riff in Van Halen’s ‘Ain’t Talkin’ ‘Bout Love’, although as they’re so closely connected, some would argue it’s closer to a flanger, which Eddie Van Halen also housed in his FX board. Either way, its imprint on the sound is iconic, and remembered by all.

This blog wouldn;t be complete without at least mentioning one of the most famous studio chorus units of all time, the Roland Chorus Echo RE-501. This unit, coming from a product line of other renowned echo units, has been a staple in studios since its creation in 1974. The combination of chorus and echo, like peanut butter and jelly, Lennon and McCartney, compliment each other so beautifully that after using something like the RE-501, it’s difficult to imagine one without the other. This unit employs an actual endless tape loop under the hood so to speak, so where many FX units will claim to be “analog”, they may actually be more of an imitation compared to the none-more-analog approach of utilising a physical piece of analog tape to create the effect. This kind of unit has a beautiful shimmering quality that works well on so many instruments, not just guitar and vocals. Have you ever put a chorus echo on a top line percussion track? If not, go do it now, your hi hats will thank you.

So the chorus effect, and its not so dissimilar offshoots flange and phase, have deep roots in the history of recorded music. The chorus is the recreation of a natural phenomenon when signals are almost perfectly aligned, but not quite perfectly enough, so there is an audible effect at play. It’s a human-like effect that we’re all used to hearing, as no two real world sources are ever really perfectly identical, be there differences in pitch, timing, acoustic environment or any number of other factors. Over time this effect has been utilised by many artists either as a guitar effect or on dream-like FX drenched vocals. It’s a sound that we all know and love, and long may it continue to be.